The highest performing companies are those that can deliver profitable year-over-year organic growth. Innovations are a key element for sustainable growth by enabling companies to acquire new customers and keep existing ones. The question for businesses is: How can you measure the effectiveness of the innovation ecosystem for delivering sustainable organic growth? Unfortunately, organizations often simplify innovation performance measures to just a few metrics which do not produce sufficient learning and continuous improvement. An innovation ecosystem has many components including multiple innovation types that require different innovation processes each with many phases and views necessary at the portfolio, pipeline and project. It’s not surprising that having just a few performance measures does not provide sufficient dynamic range to enable continuous improvement and sustained growth. Effectively measuring innovation is an ongoing challenge for most organizations. In fact in a recent 2019 Gartner report, the inability to measure innovation impact was the second most cited barrier for organizations to committing to investing in innovation[1]. Additionally, businesses typically use metrics (i.e. profitability or market share) that measure only what has happened, not an indicator of what will happen as outlined in a recent article from BCG[2].

Whilst there are many innovation performance metrics that can be deployed, some can harm the innovation process and the overall company if not enough thought goes into putting them in practice. The performance measures need to be designed appropriately for the element of the innovation ecosystem. In contrast, large corporations often distill innovation performance down to one simple metric. For example, the New Product Vitality Index (NPVI) is often measured and is the percent of revenue from innovations launched in the last 5 years divided by the total revenue[3]. A high percentage (i.e. 30% for B2B Companies) is generally correlated with a healthy innovation practice. It is often assumed that a high and increasing NPVI will generate growth because the company’s new offerings are delivering value and being adopted by customers. Although on paper NPVI may be considered a good measure for a company’s innovation ecosystem’s performance, in practice it provides an incomplete growth picture. For example, from 2011 to 2015 a large Fortune 100 enterprise had an NPVI of 32-33%, yet the revenue compound annual growth rate over this time frame was only 0.6%.

The challenge with NPVI is many fold. First, NPVI is a result indicator, an aggregate of many innovation activities and not a future predictor of growth. The innovation process is complex and it’s unlikely to be measured by only one metric. Second, NPVI is the result of all types of innovations and not all types produce the same top line growth. For example, if the new innovations are just re-makes of existing products, product improvements or line extensions they may only sustain the same market share and have limited top line growth. Alternatively, innovations introduced into new markets could be 100% accretive growth. Let’s review some of the pros and cons of NPVI.

Pros

- Simple single number related to innovation and the % revenue obtained from newer products

- Easy to measure; track innovations launched within the last 5 years, quantify innovation revenue as a % of total revenue

- A common metric in large B2B companies and because NPVI is summarized in a percentage it is easy to compare against other companies

Cons

- Provides only a partial view of the revenue picture; innovation revenue is only a percentage of the total revenue and one needs to know all the revenue components to understand the interplay between the components and their growth contribution

- The percentage is market dependent, for example markets with short replacement cycles (consumer electronics) can be very high versus markets that have long adoption cycles (medical) and can result in very low NPVI

- The percentage can depend on the market and technology maturity, for example mature markets or technologies may have little innovation potential (i.e. tires)

- Company NPVI definitions vary, making comparisons difficult (i.e. minor product iterations or ingredient changes can be counted in one company and not in another)

- Can be gamed and result in an increase in incremental innovations proliferating the number of products, adding manufacturing and supply chain complexity

- Innovation revenue is too generic and does not provide any insight about the innovation portfolio components. For example, not all innovation revenue has the same topline growth potential. Innovation revenue resulting from adjacent markets is accretive whereas revenue from CORE innovations may be replacement, cannibalize other products and have low to no growth

- Typically reported on an annual basis and not used to continuously improve the innovation ecosystem performance

We are not saying that NPVI is not a good indicator, we are only concluding that NPVI can’t be used as the only indicator used when assessing the innovation performance of a company. For a clear picture of the innovation ecosystem performance, future outlook and decision making a more comprehensive set of indicators are needed. Indicators that will complement the shortcomings of the sole use of NPVI. The ideal metrics dashboard would include a mixture of portfolio, pipeline and projects, easy to track and they will enable continuous improvement of the ecosystem. The indicators need a high degree of alignment across all levels of the company. Furthermore, there are certain prerequisites needed to make the NPVI useful (less prone to misleading) and an integrated part of this dashboard.

Prerequisite 1: the company should agree on a definition of innovation and message their intentions and priorities

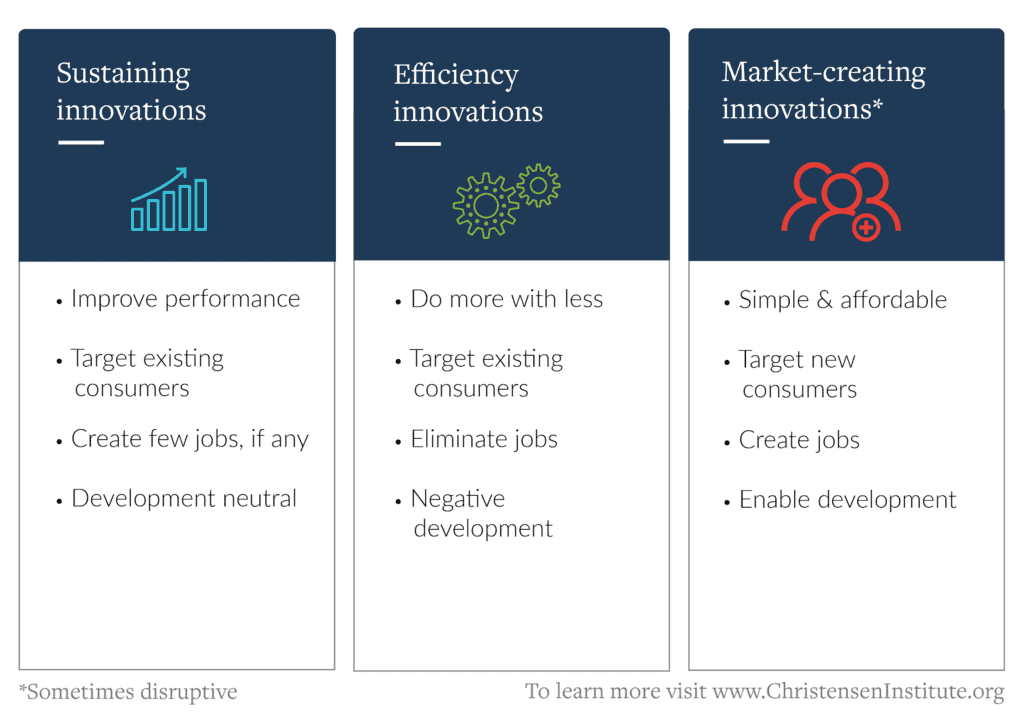

There is not just one type of innovation. Innovation can be broken down into 3 main types, each with their own goal and summarized in Figure 1[4],[5]. The first type is “Sustaining” innovations where incremental changes are done to make existing products better. For this innovation type the market and customers are known and the business model is proven and repeatable. A good example of a sustaining innovation is the most recent iPhone 12 product launched in October as it was an incremental improvement over the previous year’s model. These innovations are important because if Apple did not continuously improve on the previous year’s product, they would lose their leadership market position, their market share would decrease and see declining revenue. The business impact of sustaining innovations can vary from increased revenue growth where the differentiated products continue to address unmet needs and gain market share to negative growth where they are undifferentiated and deliver little to no new value. Next is “Efficiency Innovations” which help the company sell mature products at lower prices and improve productivity and profitability, freeing up cash flow. Essentially doing more with less. For example, Toyota’s production system allowed it to operate with a much lower inventory level.

Sustaining and Efficiency Innovations are key growth drivers for the CORE enterprise business. The third type is “Disruptive” or Market-Creating Innovations that reduce the price so substantially that they create a new market or class of consumers as shown in Figure 1. For example, itunes brought affordable music to the masses. Market creating innovations can generate accretive revenue (i.e. iTunes) but may also cannibalize existing markets (i.e. Netflix streaming content cannibalized DVD movies). From a business growth perspective, sustaining and efficiency innovations can add accretive revenue to the enterprise as they may enable the company to penetrate new markets and applications. Innovations can move through all innovation types. For example, the iPhone was a disruptive innovation because it disrupted personal computing by providing a low-cost alternative that fits in your pocket, but over time the innovation is not creating new markets and the innovations become sustaining. As the product matures further, efficiency innovations become dominant and reduce costs further. Successful companies recognize that each innovation type has a role for sustainable business growth and will take a portfolio approach.

Without a clear definition of innovation agreed upon by everyone in the company NPVI will be a confusing measure as everyone will refer to different things when they measure NPVI at business unit level.

Prerequisite 2: align expectations with the risk of disruption.

Historically speaking most companies were disrupted because of their inability or unwillingness to expand beyond the core business – too much focus on execution and not enough investment in search. Cautionary tales like Blockbuster vs. video streaming or Kodak vs. digital photography are here to warn leaders of the dangers of fully committing to the exploit part of the organization to the detriment of the explore side.

One of the best ways for companies to get an idea of the threat of disruption they find themselves unders is to get a clear picture of their portfolio (and constantly manage it against changes in the market, stakeholder expectations and vision).

Manage the Portfolio

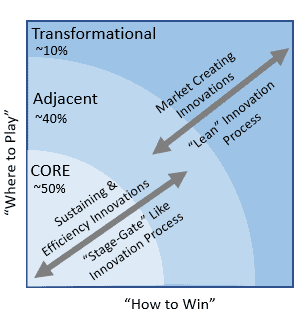

For sustainable growth, the enterprise needs to take a portfolio approach with an appropriate mix of innovations that serve the CORE markets & customers with existing products & assets, Adjacent markets & customers with incremental products & assets and completely new to the world markets with new products & assets. The portfolio of choices are made along the “How to Win” (Products and Assets) and “Where to Play” (Markets & Customers) axis of the Ambition Matrix and is described in detail elsewhere[6],[7].

The resource allocation for businesses is approximately 50%, 40% and 10% in CORE, Adjacent and Transformational regions respectively. However, each company or line of business must determine the appropriate allocations across the ambition matrix that are aligned to their strategic intent. Resource allocations include those individuals responsible for innovation such as R&D, Customer Insights & Discovery, Business Model Innovators, Agile Project Innovation Teams, Launch Coordinators etc. As described in the previous section sustaining and efficiency innovations are typically in the CORE and near adjacent. Disruptive or market creating innovations may fall in the far adjacent and transformational. Figure 2 shows where the innovation types and the associated innovation processes typically fall on the innovation ambition matrix.

Therefore before deciding to use the NPVI part of the ecosystem’s dashboard, the leadership team needs to decide where they are expecting the new products to be created, and where is NPVI measured. Ideally measuring NPVI will become a proxy for the risk of disruption if NPVI is measured for adjacent and transformational initiatives (low numbers meaning that the company is not investing enough in new beyond the core idea or they lack the skills to bring beyond the core ideas to market). For further fidelity the leadership team can decide to take NPVI samples from each of the 3 areas of the portfolio therefore having 3 indicators (NPVI Core, NPVI adjacent, NPVI transformational) that provide added clarity to where investments are happening.

Measure Appropriately

However these prerequisites are not going to be enough and as stated earlier, NPVI needs to be complemented with other indicators to get a better diagnostic on the company’s innovation performance. To do that we first need to clarify the fact that NPVI is a result indicator and not a performance indicator. Oftentimes one uses the term “Key Performance Indicator” (KPI) for any type of business metric. However, not all measures are Key Performance Indicators. In his research, spanning 30 years, David Parmenter has identified 4 types of indicators: result indicators, performance indicators, key result indicators and key performance indicators as described below[8]. Knowing the different types of indicators will help determine the best measures throughout the innovation system.

Result Indicators (RI) – measures that are the summation of many teams’ inputs and are helpful for looking at the combined effort. However, they do not help management fix a problem as it is difficult to determine which team is responsible for the performance or nonperformance. All financial measures are result indicators. Some examples include: NPVI, innovation revenue, number of ideas in the pipeline, future accretive revenue etc.

Performance Indicators (PI) – measures that are associated with a team or small cluster of teams that work closely together for a common purpose. These measures have good clarity and allows management to determine the team responsible for the performance or nonperformance. Some examples might include: number of customer discovery projects completed last month, number of coaching hours booked for next month, number of customer interviews last week.

Key Result Indicator (KRI) – Typically reviewed monthly or quarterly and give management a good view of how the organization is progressing. KRIs are always a past measure and they do not tell you what to do to improve the results. Typically KRIs are shared at high level meetings (i.e. Growth Board) to highlight how the innovation ecosystem is performing. An example of a KRI would be NPVI or portfolio revenue expected in 3 years or Year-over-year innovation growth.

Key Performance Indicators (KPI) – these are critical for the current and future business success. KPIs are non-financial, measured daily or weekly, team based and have a significant impact on the business success and are fundamental to the organization well-being. KPIs should not be linked to pay for performance to avoid undesired manipulation. Examples could be in the discovery phase of the innovation process, the number of customer interviews last week or in the launch phase the number of innovation engagements with customers.

The different performance measures above highlight that to have a comprehensive way of measuring the innovation ecosystem performance you will need a mixture of Result and Performance Indicators. The PIs and KPIs will highlight the performance of teams and provide a more direct means of improving the two types of innovation processes, whereas the RIs and KRIs will highlight more of an aggregate view of how the organization is performing and would be seen at the innovation portfolio level.

Therefore, since NPVI is a result indicator it needs to be complemented with performance indicators that are quicker to be measured and influenced. These process indicators need to be inline with the company’s agreed up innovation development process.

There are two basic types of innovation processes, one for relatively low uncertainty innovations and another process for high uncertainty requiring rapid learning. Typically, disruptive (i.e. innovations that target new adjacent markets) have high uncertainty, whereas efficiency and sustaining innovations have low uncertainty. There are many excellent resources describing these two innovation processes[9],[10],[11].

The innovation processes for low uncertainty innovations can be broken down into 3 main phases; discovery & business opportunity, development & validation and launch and is described in more detail elsewhere and typically resembles a Stage Gate process. The earliest innovation phase is discovery where resources are allocated to understand customer jobs to be done, customer problems, unmet needs and size of the opportunity. The next phase is test and development where the prototypes are tested and the value proposition is verified by the customer. Depending on the evidence that the value proposition resonates with the customer, multiple iterations may be tested before you are ready to move to the next phase. The launch phase is where the offering is brought to market capturing customers and revenue.

For high uncertainty innovations such as disruptive and innovations that are outside the core markets requires an innovation process that is more learning based using lean principles. Typically for the lean innovation process, the phases are discovery of opportunity areas, prototyping & validation, incubate and scaleup. The discovery phase requires rapid learning with focus on customer problems and unmet needs.

However, in this phase the project team is exploring new to the company markets and large customer problems requiring agile learning processes. In the prototyping & validation phase there are typically many cycles of rapid prototyping, evaluation and learning. Once the business model is verified the innovation can be scaled. The investment for high uncertainty innovations is “metered” depending on the level of uncertainty, much like the VC investment in startups with seed stages and series funding.

Both innovation processes will have metrics focused on customer problem discovery, evaluation of value, time spent in a phase and the ability of the team to achieve their project commitments. For the stage-gate process the team commitments will be predominately execution whereas for the lean innovation process the team commitments will be mostly learning based.

This being said the NPVI result indicator can be very well complemented with performance indicators for the innovation process such as:

- Number of ideas generated

- Learning velocity

- Time in stage

- Percentage of ideas progressed from stage to stage

Take for example a company that wishes to lunch a minimum of 5 new ideas in the next fiscal year. If the half way through the year there are no new ideas submitted and kickoff, the chances for the company to reach their goal are slim. Or if ideas are being generated but they don’t pass the first stage of the product lifecycle (Percentage of ideas progressed from stage to stage) from the lack of in-market validation (Learning velocity and Time in stage), again the chances of the NPVI goal being hit are slim.

The goal for deploying any metric is to, on one hand inform decisions and on the other help the company improve. However, given the complexity of modern organizations and the environment they operate in, it is very difficult to get an accurate picture by using just one single metric or just by measuring one layer of the company’s value creating system. Metrics need to be interconnected and mutually supporting if they are to be useful. A system of metrics needs to be able to clearly communicate to one layer of the company what is happening at another layer. Furthermore it needs to do this efficiently therefore allowing decisions to be taken at speed. What metrics make up a company’s metrics system and how each metric is defined is at the end of the day connected with the company’s overall vision and ambitions for the future. The Annex at the end of this article illustrates an example of how a company can connect the different levels of metrics from the innovation goals to the portfolio, pipeline and projects.

Summary

NPVI, like many other metrics has limitations, therefore it cannot be used as the sole metric when trying to understand the healthiness of a company or its future onlook. By mitigating it’s shortcoming through added clarity and the addition of other supporting indicators (measurements), NPVI can however become a useful indicator for any leader looking to make data informed decisions with respect to their company’s innovation ecosystem.

Conclusions

- To have NPVI work in a company, the company first needs to define what it means by innovation.

- The NPVI figure needs to be aligned with the company’s future ambitions and/or its disruption threat. (NPVI needs to compensate for portfolio attrition/fade)

- NPVI is a self-benchmarking result indicator.

- NPVI needs to be considered in the context of the different types of innovation and not only as a company wide aggregate, otherwise the company might end up with more of the same products.

- It is advisable not to couple NPVI with the individual’s/management’s reward system as it might trigger undesired behaviour

- NPVI can’t be used as the sole metric to assess the healthiness and/or future outlook of a company. It needs to be complemented with performance indicators as it suffers from 3 major limitations:

- 1) It’s not predictive; it only tells you what has already happened.

- 2) It’s not prescriptive; it doesn’t suggest how to improve.

- 3) It’s not precise; is it a new product if we just change its color?

Article co-written with Dan Toma.

Annex

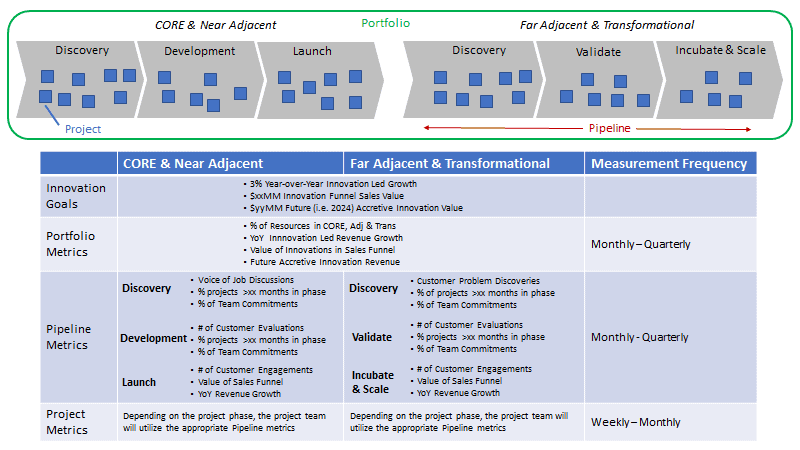

The top of Figure 3 provides an example of typical goals for innovation led growth and resource allocation across the innovation ambition matrix. From the innovation goals four main portfolio KRIs are selected; Resource allocations across the ambition matrix, the Year-over-Year (YoY) Growth, Value of Innovations in the Sales funnel and future accretive innovation revenue. The future potential accretive revenue metric provides an estimate of the future potential value to determine if the longer-term innovation led growth goals can be achieved. These KRIs can be tracked in quarterly or monthly trend charts over the past 6-8 quarters to visualize progress towards the growth goals. The innovation pipeline metrics are highlighted for the various phases of the “Stage-gate” and Lean Innovation process and are a mixture of KPIs and KRIs. In the first few phases the metrics focus on customer feedback, the innovation team achieving their monthly execution & learning commitments, velocity through the phase. In the launch and incubate phase the metrics focus on customer engagements, value of the innovation sales funnel and YoY revenue. The metrics can be measured monthly to quarterly depending on the specific metric. On a weekly to monthly basis the Individual project teams will measure the metrics associated with their current innovation phase. The innovation metrics highlighted are just an example to highlight how the metrics start with the business portfolio goals and drive further down into the innovation ecosystem to measure the pipeline phases as well as the individual project teams so the entire innovation organization is engaged and aligned to achieving the businesses goals.

[1] Gartner Report 2019

[2] Achieving Vitality in Turbulent Times, BCG 2019

[3] It is common to use 5 years as a length of time for innovations as it provides sufficient time from launch to sustainable revenue. However different lengths of time can be used and may be longer (i.e. medical industry where innovation adoption can be very long) or shorter (i.e. consumer markets where adoption is rapid or have annual product launches).

[4] The Capitalist Dilemma by Clayton Christensen and Derek Van Bever, HBR June, 2014

[5] The Prosperity Paradox by Clayton Christensen, Efosa Ojomo and Karen Dillon, 2019 (see pages17-36)

[6] Innovation Ambition Matrix – HBR Article

[7] Detonate, Geoff Tuff and Steven Goldbach, 2019

[8] Key Performance Indicators, David Parmenter, 4th Edition 2019

[9] The Lean Product Lifecycle, Tendayi Viki, Craig Strong and Sonja Kresojevic, 2018

[10] The Corporate Startup, Tendayi Viki, Dan Toma, Esther Gons, 2017

[11] New to Big, David Kidder and Christina Wallace, 2019